Palestine is synonymous with violence, but politics takes a back seat on this extraordinary new walking route where the people are welcoming and the countryside stunning

There was a moment of silence. Then the Palestinian youngsters marched in front of us and I thought to myself, this is where they sing about being martyrs and dying glorious deaths. A gentle breeze swayed the mulberry tree. On the far ridges of the mountains around Nablus, the lights of the illegal Israeli settlements twinkled. This village, I knew, had seen 2,000 acres of olive groves taken by those settlers, plus several lives. An older girl called the group to order then, in English, they launched into their chant.

"I'm a red tomato, you're a green tomato. You're a little cucumber..."

Everyone started to laugh. A walking holiday in Palestine. You've got to laugh really. I laughed a lot on that walk. And this in a part of the world where something horrible is always happening, be it shootings in Hebron, attacks on aid flotillas, or separation walls and rocket attacks. In the middle of such madness, laughter is the most unexpected and valuable pleasure, one that people seize at every opportunity.

It was perhaps appropriate that I started my hike in the far north of the West Bank, within a few miles of a hill called Megiddo, where Pharoah Thutmose III overwhelmed the Canaanite king Durusha in about 1457BC, thus beginning the legend of Armageddon, the site of the Last Battle. With my guide Hejazi, I walked through peaceful fields of wheat past other ancient sites, exploring Roman tombs lost in undergrowth and watching storks circling overhead on their migration north. Our first major stopping point was Jenin, a town whose name is tied inextricably to violence and death. Despite its reputation, however, Jenin turned out to be a friendly market town of Palestinian farmers, a place to gorge on strawberries and almonds, washed down with carob juice sold from huge ornamental brass urns.

I walked around the souk in a bit of a daze. How could reality be so different from expectations? Certainly, the walls were pockmarked with bullet holes from the second intifada, but the martyrdom posters were all faded by the sunshine and people wanted to shake hands. The carob-juice seller adjusted his Ray-Bans and grinned: "Why not join me on Facebook?"

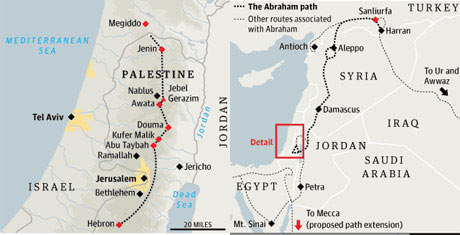

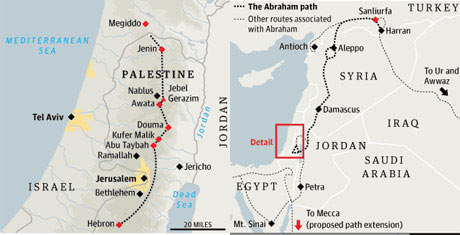

There are several long distance footpaths in Palestine, but the one I was following was the Masar Ibrahim al-Khalil – literally Path of Abraham the Friend of God, simply the Masar for short. This new route stretches across the Middle East, starting at Abraham's birthplace in Sanliurfa, south-east Turkey, and winds south through Syria, Jordan and Israel. Eventually, it could stretch all the way to Mecca, linking existing paths associated with Abraham, and new routes. Its purpose is to promote understanding between different faiths and cultures; it's also intended "as a catalyst for sustainable tourism and economic development". In places the path barely exists yet, in others it is well-worn, but everywhere it needs a guide. Hejazi was my man in Palestine, a person of unending cheerfulness and optimism.

For a Muslim, Hejazi tells me, the idea of a path named after Abraham is attractive since the great patriarch is revered as the "father of hospitality". To Jews and Christians, he is equally important – the starting point for monotheistic worship. The Masar, I discovered, is not some do-gooder peace initiative, but simply a great way to see the landscape and meet people.

The path makes no attempt to follow Abraham's original route, even if such a path could be discovered; rather it links sites that bear legends and folk tales about the man. Our first major site was south of Jenin at Jebel Gerazim, a mountain that stands above the ancient town of Nablus and affords astonishing views west to the Mediterranean and east to the hills of Jordan.

On the summit of the mountain is a tower built by Saladin and some fine, if neglected, Byzantine mosaics guarded by a group of Israeli teenage soldiers. Further down the hillside, we could see the houses of that renowned Jewish sect the Samaritans, a group that still has more than 700 followers.

"The reason the Samaritans revere this place," Hejazi explained, "is because they believe Abraham came here and built his first altar in Canaan."

It was a well-chosen spot to view what Abraham wanted: territory. "Unto thy seed," said his God, "will I give this land." And that was very generous of the Lord, all things considered. Except, of course, that all things had not been considered: previous inhabitants and the sheer fertility of Abraham's seed, which includes not only the 12 tribes of Israel but the prophet Muhammad via Ishmael, fruit of Abraham's union with the serving wench Hagar. And what about all those cousins from Noah's brothers? If Abe's God had spent a few moments considering, he might have foreseen problems.

That evening we stayed in Awata, a village near Nablus where the children sang about red tomatoes. There were tales of horror and violence too – there is no escaping the bloodied history in this land – but it never became overwhelming, as I'd expected. Hassan, our host, was keen to enthuse about the Masar: "It was like a light coming on here," he said. "We got connected to the outside world and that makes us feel hope. Everyone in the village is always asking about when the next walkers are coming."

Like most Palestinian villages, Awata has long since burst out of its ancient walled settlement and sprawled along the hill. But what is fascinating is that, amid the concrete and graffiti, there are sudden glimpses of an ancient world. When we chatted about water resources, Hassan jumped up and hauled open a trapdoor under our feet. Below us was a vast echoing cavern. "It's a Roman water tank," he explained. "We've got three of them."

After a huge feast of chicken, freshly made bread, pickles, salads and yoghurt, Hejazi and I bedded down on mattresses in the living room and slept.

Next morning we started out at 8am, meandering through olive groves and wheat fields. Scents of Persian thyme, wild sage and oregano drifted up from beneath our tramping feet. We stopped at a spring to drink delicious clear water, then pressed on, meeting other walkers as we climbed through meadows of scarlet poppies and butterflies to Jabal Aurma, a bronze age fortress. One of the shocks of doing this path is that the countryside is lovely. Travellers have been returning from the Holy Land with scornful appraisals of its beauty for many centuries. Herman Melville is typically bleak: "Bleached-leprosy-encrustations of curses-old cheese-bones of rocks," he wrote. The image of an ill-fated land has proven hard to budge.

On top of Jabal Aurma we discovered six vast underground storage rooms carved from solid rock, presumably to supply the fort during prolonged sieges. There is never any doubt in Palestine that this land has been a chaotic crossroads for civilisations, armies and tribes for a very long time – that is what makes it fascinating and worth exploring.

Later that day, we emerged on the edge of a grand escarpment looking down to the Jordan Valley, around 800ft below sea level. The wheat fields around us were tiny rocky terraces splashed with the yellow of wild dill. It's a difficult place to farm, and we came across Shakir Murshid with his wife and six children busily harvesting wheat by hand. On a sage bush nearby was the complete shed skin of a viper.

That night we stayed in Douma, a cluster of old stone dwellings long since overgrown by the straggling concrete of modernity. Rural life, however, was pretty much the same as ever: woodpeckers tapped at the trees, wheat fields surrounded the houses and men rode past on donkeys. We spent the evening by a campfire listening to locals sing and play homemade flutes. The patch of flat ground where we had built our fire turned out to be a Roman wine press, empty sadly. Once again we slept in someone's living room, under the eyes of family martyrs.

Our third day took us further south near the springs of Ain Samiya, now a water source for Jerusalem. We spotted chameleons in the bushes, whistling rock hyraxes and huge flightless crickets, then clambered up a delightful gorge, taking narrow shepherds' trails along the cliff face. By evening we approached the village of Kufer Malik, a place that was to hold perhaps the biggest surprises. The first came at a huge hacienda-style house, where the whole family came out to invite us in for coffee. "Do you speak Spanish?" asked the husband. "I learned it in Columbia."

Kufer Malik, bizarrely, is a little enclave of Latin America in Palestine. When we found our hosts for the night, the old man of the family, Hosni al-Qaq, explained: "In the 30s when times were hard here, my uncle decided to seek his fortune in America. He ended up selling shirts in Columbia, then got a shop and then a supermarket. He became very rich." Hosni smiled ruefully. "My father on the other hand stayed behind and was killed in the first intifada."

"And did other men go?"

"Oh yes, lots and lots, and then they spread out into other countries. There are now more than 800 descendants of this village in Brazil alone."

The effect of this exposure to the outside world on Kufer Malik has been electrifying. The men are hard-working and ambitious; the women assertive and independent-minded. Hiba, our hostess, had been to the Côte d'Azur to see what it was like. "We camped on the beach in Nice," she said proudly. "It was lovely."

So was her cooking: roast chicken, rice, vegetables and musahn, a flat bread cooked with sumac and onions.

"What would you do if a Jewish person came to stay?" I asked.

"No problem," they all said eagerly. "We've had one Jewish lady from America already and another from Brazil. Everyone is welcome here."

After dinner, the men sat out in the yard smoking shisha pipes. When they spoke Spanish, they looked like pure Columbians to me: all macho body language and grand gestures. When they spoke Arabic, they were Palestinian farmers again.

Our fourth day took us to Abu Taybah, home to the West Bank's only brewery – owned and run by a Palestinian Christian family (there are around 55,000 Palestinian Christians). After a glass of deliciously cold lager we moved on, walking down Wadi Qult to the marvellous fourth-century cliff-side monastery of St George, then on to Jericho.

The end of the Masar comes in Hebron, whose old city has been a dangerous flashpoint over the years. Zionist settlers have seized buildings in the market area – which has to be roofed with netting now to prevent rocks and rubbish raining down on shoppers. All of Abraham's progeny want a piece of the action here and the mosque has been forcibly divided to create a Muslim and a Jewish section. On one side, I found Indian Muslims praying and taking photos; on the other Jews from New York and Tel Aviv were doing the same. The Tomb of the Patriarchs, of course, looks pretty similar from either angle, though neither community, sadly, ever gets to see that fact.

Out in the street a shopkeeper invited me to have coffee. He was sitting with Micha, a former Israeli soldier turned peace activist, a young freckle-faced man with a friendly smile. What had convinced him to adopt what many Israelis see as a traitorous approach?

"Small things. It started when I was a soldier, talking at checkpoints to Palestinians, seeing what the settlers were doing, and what we were doing to protect them."

At that moment a Palestinian lady came over. They introduced themselves. "So now you work for peace?" she asked. "But I have to ask: did you kill any Palestinians?"

Around the shopfront where people were taking coffee and chatting, everyone froze. There was a long silence while Micha considered his reply. "I'd rather not say."

"I think you should," the woman said. "For any reconciliation, you have to."

A murmur of agreement passed through the small crowd. Micha thought again. "The truth is, I don't know. At Abu Sinaina we did shoot, but it was from far away."

"At Abu Sinaina? Then you killed at least five."

There was a pause and then Micha nodded. The Palestinian lady smiled. "You are welcome at my house. You must come for lunch."

They exchanged addresses and Micha promised that he would visit.

What is remarkable about the Masar walk is that religion and politics mostly take a back seat, allowing ordinary people to climb out of the foxholes of prejudice and suspicion. When that happens, Palestine becomes so much more than a brief and violent television news clip. I saw gazelles running on hillsides, tasted the local cuisine and enjoyed conversation on everyday topics. I climbed down inside bronze age burial chambers, tracked hyenas into their lairs inside Roman tombs and lay on the benches in Nablus's marvellous Turkish baths, discussing the best way to pickle olives. The problems of Israel's land-grabbing tactics remain: the wall is still standing and unsmiling teenage soldiers at checkpoints demand to see passports.

The Masar is not for those who want private rooms or special treatment. It is intense and sometimes emotionally draining. There were moments when I felt rage about the injuries and injustices. But, more than anything, this was a life-affirming and exhilarating experience that will stay with me like few others.

Way to go

Getting there

Jet2.com flies from Manchester to Tel Aviv, from £99 one way. A four-day walk along the Masar (abrahampath.org/palestine.php), including guides, home-stay accommodation and meals with families, costs £400pp (or £570 with two nights in Jerusalem and one in Bethlehem). Tours are run by Palestinian operator, the Siraj Center (+972 2 274 8590, http://www.sirajcenter.org/, email michel@sirajcenter.org).

Further information

Check the Foreign Office website (fco.gov.uk) for travel advice on Palestine.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010 at 06:47PM

Tuesday, November 2, 2010 at 06:47PM  APJP | Comments Off |

APJP | Comments Off |