Racism and discrimination key to Jewish hegemony in Jerusalem

Wednesday, December 26, 2012 at 11:17PM

Wednesday, December 26, 2012 at 11:17PM Ben White 15 December 2012 Middle East Monitor

Imagine if the mayor of a major British city declared it official policy to keep the number of ethnic or religious minority residents as a proportion of the population below a certain ratio. In Jerusalem, this is not a hypothetical nightmare but the reality under Mayor Nir Barkat.

In 2010, Barkat told a Knesset meeting that the number of Palestinian residents in Jerusalem poses a "strategic threat", citing a 70-30 Jewish majority as "the government's goal". Aspokesperson later asserted the mayor's belief that "Jerusalem should remain a city with a Jewish majority" (a position Barkatconfirmed himself in a 2011 BBC interview). A US diplomatic cable noted that the mayor's "comments reflect long-standing [Government of Israel] policy regarding the desired demographic balance in Jerusalem".

Barkat's views are not exceptional for his office. His predecessor Ehud Olmert, speaking in 1998, considered it "a matter of concern when the non-Jewish population rises a lot faster than the Jewish population". Aides to the late Teddy Kollek, mayor from 1965-1993, "admitted that during his decades in office, the city's master plan was aimed at preserving the population balance at 28 per cent Arabs and 72 per cent Jews".

In 1970, Kollek helped to put together a plan containing "the principles upon which Israeli housing policy in east Jerusalem is based to this day", namely: "expropriation of Arab-owned land, development of large Jewish neighbourhoods in east Jerusalem, and limitations on development in Arab neighbourhoods".

Those are not the words of a Palestinian activist or NGO with an "agenda" - that is the verdict of Amir Cheshin, former senior advisor on "Arab Affairs" for ten years under Kollek and then Olmert, who wrote about the reality of the 'united' capital in his book 'Separate and Unequal'.

In Jerusalem, constantly touted by Israel's leaders as the country's "eternal" capital, Palestinian residents in the illegally-annexed East of the city face planning restrictions, home demolitions, discrimination in municipal services, and the community-shattering Apartheid Wall.

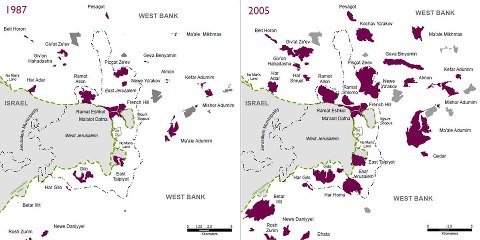

Since 1967, Israel has expropriated a third of the annexed land for the construction of illegal settlements, which now have a population of around 200,000. Only 13 Per cent (another figure is 17 per cent) of the Israeli-annexed area of East Jerusalem is 'zoned' for Palestinian construction, successful application permitting of course. An EU report in 2009 noted that the Palestinian Silwan neighbourhood had received only 20 building permits from the Israeli-led Jerusalem municipality since 1967.

In another area of the city, Sheikh Jarrah, Palestinians have been evicted from their homes so that extremist religious Jews can move in, a phenomenon described by former Israeli Tourism Minister Benny Elon as "a microcosm of the entire story of Jerusalem". These settlers claim ownership of land from pre-1948 - which even if true, is ironic given that none of the estimated 45,000 Palestinians expelled from western areas of Jerusalem in the Nakba can regain their property using similar, more valid, claims.

Barkat presides over a city divided by Israel's Separation Wall, with tens of thousands of Palestinian residents on the 'wrong side' and forced "to pass through checkpoints on a daily basis in order to get to work, attend school, obtain medical services, visit family, etc". Earlier this year, it was revealed that a senior official in the municipality had asked the Israeli military "to take responsibility for handling civilian matters pertaining to Jerusalem residents east of the separation fence".

In 2010, city councillor Yakir Segev described the Palestinian areas east of the Wall "no longer part of the city", and admitted that the "separation fence... was built for political and demographic reasons - not just security concerns". Last December, Barkat himself publicly proposed "relinquish[ing] areas of the municipality that are located outside of the fence" in a plan that, "according to a municipal source", would mean "a very small territorial gain for Jerusalem, with a loss of approximately 40,000 Arab residents".

That's not the only way that the Jerusalem municipality seeks to address the 'demographic threat'. In 2008, Israel stripped over 4,500 Palestinians of their residency status, a figure which is a third of the total revocations since 1967. An EU report in 2005 observed that when it comes to the residency status policy, "Israel's main motivation is almost certainly demographic".

A 2006 publication by current Jerusalem city councillor Meir Margalit details the discrimination at the heart of Israel's self-proclaimed undivided capital. East Jerusalem gets 12 per cent of the city's welfare budget, 15 per cent of the education budget - and the pattern repeats itself.

The facts and figures are clear. In order "to try to guarantee a Jewish majority and generate Jewish hegemony in Jerusalem", Israel "has annexed huge parts of Jerusalem, enlarged the boundaries of the municipality, taken lots of land in the eastern part of the city and built more than 50,000 housing units on this land exclusively for Jews". Those are the words of the director of Israel's Macro Centre for Political Economics.

Jerusalem's official racism - where, in the words of former deputy mayor Meron Benvenisti, "an ethnic population ratio serves as a philosophy" - is emblematic of Israel as a whole. Palestinians facing daily discrimination and segregation don't need expressions of 'regret' or another statement of condemnation - they need action, so that there is accountability for policies that would be considered unacceptable anywhere else.

APJP |

APJP |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |