Arab villages, bulldozed from our memory

Saturday, September 1, 2012 at 11:19PM

Saturday, September 1, 2012 at 11:19PM Our beloved Tel Aviv, whose reputation for enlightenment and openness is world renowned, is built in part on ruined Palestinian villages - and refuses to acknowledge it.

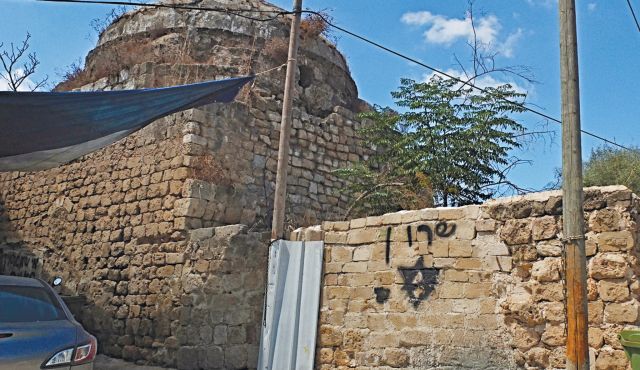

By Gideon Levy Aug.31, 2012 Haaretz  Remains of a mosque in Salama, now Kfar Shalem. Photo by Alex Levac

Remains of a mosque in Salama, now Kfar Shalem. Photo by Alex Levac

A small metal sign adorns the tiny power station at the center of Jerusalem Boulevard, Jaffa: "T.P. Faisal." It's testament to a recent past that has been erased.

T.P. is easy: it stands for command station in Hebrew. And Faisal? Negligence on the part of some clerk left physical evidence of the original name of the adjacent Yehuda Hayamit Street on a machine. Faisal Street briefly became 54th Street, and shortly thereafter Yehuda Hayamit Street.

"Yehuda Hayamit" is the name given to a rare Roman coin that, in time, was revealed to be a fake. So, in order to suppress the memory of the recent past of Palestinian ruins, the names of the sites are exchanged for names that hint at a more distant past. In other words, switch the king with a coin, even if it's counterfeit.

I wouldn't have noticed the sign had it not been for the new guidebook "Omrim Yeshna Eretz" ("Once Upon a Land," published by Zochrot and Pardes Publishing). It is a bilingual tour guide, in Hebrew and Arabic, to what is left and - mainly - what was erased, almost without a trace. A journey through time and consciousness, 18 tours to some of the approximately 400 Palestinian villages and urban neighborhoods, whose residents fled or were expelled in 1948. Most of their homes were wiped off the face of the earth immediately afterward, generally without even a sign remaining of them. This guidebook arrives now to remind and acquaint, though it is doubtful whether many Israelis will take its tours. After all, the Nakba - the "catastrophe," as Palestinians call it - has practically been outlawed here.

This week we followed the book's walking tour of underground Tel Aviv - the city that in 2012 is still afraid to mention on its official logo what it is called in the language of its Arab residents. From Yaffa to Shaykh Muwannis, via Salama, Al-Manshyya, Summayl and Jamassin; from Jaffa to Ramat Aviv, through Kfar Shalem, the City, Givat Amal and Bavli, as they were renamed. Yes, even our beloved city, whose reputation for enlightenment and openness is world renowned, is built in part on ruined villages, and it is unwilling to acknowledge it.

Jerusalem Boulevard, which grew increasingly ugly over the years, until it became the ugliest boulevard in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, was once Jamal Pasha Boulevard, and also Al-Nazha Boulevard. "The King Messiah is in Israel," it says on the bus crossing the boulevard, blowing clouds of smoke on the ficus trees. We won't dwell on the streets named after rabbis in the Arab city that became mixed, yet where there are barely any streets with Arab names.

We turned into the nearby village of Salama, aka Kfar Shalem. There, betwixt the new apartment towers and old invaded homes, the past still peeks out. The main street is named for Mahal, a Hebrew acronym for the overseas volunteers who fought here during the 1948 war, in which the village was abandoned and destroyed. Some 7,800 people lived here. "Kahane was right," reads the slogan smeared on the wall of the abandoned mosque. Israel does not violate the sacred sites of other religions. In recent years a hidden hand made several holes in the mosque's dome. Entrance to the mosque is barred on all sides.

The Shamrock Group of Los Angeles built a public garden, a contribution to the community. In the playground nearby, use of the equipment is permitted from age 14 and up. According to the testimony of refugees from the Arab village, the Yatim family, a cemetery stood here. If, in Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University is currently building its new dorms on the grounds of the old Shaykh Muwannis cemetery - only part of which has been fenced off, and left neglected, off the parking lot of a sensitive security facility - then why should we complain about a Kfar Shalem playground that arose on graves? Amid the ancient eucalyptus trees, there is no remnant or sign of those graves. At the entrance to the playground, a notice marks the end of the 30-day mourning period for the late Yisrael Rosh Hodesh.

The home of the mukhtar, or village elder, does remain standing, but only the verandas remain of the Arab construction. All the rest is whitewash and add-ons, just like a sizable number of the neighborhood's invaded homes. The mukhtar's house can be found on Asa Kadmoni Street (named for a major and combat soldier in the Paratroops ), at the corner of Harahag Yosef Tzubiri (the chief rabbi of Yemenite Jewry ). The old village school is now a municipal rehabilitation institution. The apartment tower now going up on the edges of the former village is called "Tel Avivi - your corner in the city."

Northwest of here was the Al-Manshyya neighborhood: 12,000 residents in 1948, 20 coffeehouses, 14 carpentry workshops, 12 bakeries, 10 laundries, four schools, three bicycle stores, three pharmacies and two mosques - only one of which, Hassan Bek, is still standing.

"This tour was written for my daughter, Amalia. She is 4 years old today," Norma Musih, one of the editors, states in the book, "but I've been thinking about how I would tell her about Al-Manshyya ever since she was born. I want her to know that here in Tel Aviv, by the sea that she loves so much, there was once a neighborhood in which children like herself lived, people who had full lives, desires, hatreds, loves and dreams. I want to tell her, without burdening her with the terror of the expulsion and the destruction. I want her to know, but I also want to protect her. That is why I am writing this tour for her."

Of the sea of buildings visible in the old photograph by Kurt Brammer, only Hassan Bek mosque, the Etzel Museum and the train station remain. The park is called Gan Hakovshim (Conquerors' Park ), as is the parking lot and the adjacent street. At least a modicum of honesty. Alongside them rise the towers of Tel Aviv's "City." "When I look at these homes, I can imagine for a moment also the missing homes that once stood beside them," Musih writes. "Can you picture the houses that reach from Neveh Tzedek all the way to the sea? ... Let's close our eyes once and imagine how this whole place could look like if the people who lived here and their families were to return."

The Turkish-built train station - because only the Ottomans have left a trace here - is now the prime yuppie site of Tel Aviv, known as Hatahana. The historical signs and antique photographs tell of the Turks and Templers who were here. Not a word about the Palestinians. But what are those crowded houses visible in the station background, in the photographs hanging on the beautifully restored buildings? Al-Mahta neighborhood, the station neighborhood, where Arabs resided. Meanwhile, there is a new enterprise at Hatahana: a digital journey into the past, and also "Dancing at Hatahana," every Thursday.

North of there, Summayl: 190 homes before the 1948 war, farming and citrus trees, a school (destroyed ), cemetery (destroyed ) and sheikh's tomb (destroyed). Mitham Semel, they once tried to call it. Now you find Migdal Ha'mea, the Histadrut labor federation buildings, Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium and the Heichal Yehuda synagogue, on the kurkar sandstone tel that was once a village. The nucleus of the village actually remained on the kurkar cliff; now it is a pile of single-story homes whose legal present is unclear, their future shrouded in mist and their past whitewashed. Only a blackberry bush, in the heart of the bustling metropolis, provides a reminder of bygone times. "Tel Aviv is down there, not here," comes the cry of one resident who tries to get rid of us. Here they don't like people with cameras and notebooks.

As in Salama, so it is here, in Jamassin and Shaykh Muwannis: the Arabs' homes turned into Jews' real estate disputes. On the synagogue's bulletin board hangs an invitation to attend a ceremonial redemption of the firstborn donkey with Rabbi Yisrael Lau. North Tel Aviv, 2012.

Northwest of there, not far from the luxury Akirov Towers, are the remnants of the "buffalo towers" village, aka Jamassin. "We recommend that you wander around between the low homes," the book writes, "amid the local vegetation that is reminiscent of a wild jungle, and try to imagine how, more than 60 years ago, hundreds of Palestinians lived here who are no longer here today." The present-day shantytown neighborhood on the site, Givat Amal, lies hidden on the cliff, at the foot of the Yoo Towers.

In contrast to other villages, nobody knows for sure where Jamassin's 1,200 refugees fled to from here. Now it serves, among other things, as a car graveyard: countless junked autos hide in the reeds and among the brambles. The houses are fenced, giving the semblance of a Brazilian favela, with a few tidy gardens behind the fences, and a sea of warning signs - No Entry, No Parking, Barking Dog, Private Property - exactly like in Salama and Summayl. Here, too, the whitewash, the renovations and the expansions have completely covered the original Arab construction.

Finally we drive to Shaykh Muwannis. My home stands on the village's land; the irrigation pool of Pardesiya is the pool I swim in today. I've already written enough about this over the years. In the wake of a letter I received, exactly three years ago I met with the elderly Salah al-Muhur, a refugee from Shaykh Muwannis, who now lived in the tiny village of Al-Hafira, near Jenin. "Are you Levy?" he asked me on the steps of his house. "Maybe you know Levy from Kiryat Shaul, who was a bus driver? We were friends for many years." Muhur dreamed of visiting the village of his birth one more time, but his dream went unfulfilled.

APJP |

APJP |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |

Reader Comments