Capital Murder - Jerusalem's Final Status

Monday, February 22, 2010 at 10:55PM

Monday, February 22, 2010 at 10:55PM First and foremost, united Jerusalem, which will include both Ma’ale Adumim and Givat Ze’ev — as the capital of Israel, under Israeli sovereignty…

– Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, on the vision for a “permanent solution”, 5 October 1995

Jerusalem is the eternal capital of the Jewish people, a city reunified so as never again to be divided

– Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, 21 May 2009

The current consensus in the international community is that East Jerusalem, occupied by Israel since 1967, is the capital of a future Palestinian state. Israel’s unilateral annexation of territory to create expanded municipal boundaries for a ‘reunited’ Jerusalem was never recognised.

Over the last forty-three years, Israel has created so-called ‘facts on the ground’ in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), in defiance of international law. Since the Madrid/Oslo peace process, successive Israeli governments have continued to colonise Palestinian land at the same time as conducting negotiations.

The extent and scale of Israel’s illegal settlement project across the West Bank, as well as the road network, the Separation Wall, and other ways in which Israel maintains its rule over the OPT, has led some to believe that the creation of an independent, sovereign Palestinian state is impossible.

Perhaps one of the clearest indicators that there is no Palestinian state-in-waiting under Israel’s regime of control is East Jerusalem.

Israel has three, inter-related strategic goals for East Jerusalem:

- To make the claim that Jerusalem is the ‘eternal, undivided Jewish capital’ a physical reality.

- Increase the Jewish presence/decrease the Palestinian presence (‘the demographic battle’).

- Cut off East Jerusalem from the West Bank.

These are not new, but over two decades – and perhaps especially in the last few years – there has been an acceleration of the tactics being used to realise these goals. The rest of this article will provide a simple, by no means comprehensive, overview of Israel’s policies in East Jerusalem that have effectively killed the possibility of establishing a Palestinian capital.

Mapping the land and creating colonies

Since 1967, Israel has created a number of settlements in the unilaterally expanded city boundaries, with a current population of over 180,000. This represents an expansion of 65% since 1987, while the land taken up by the East Jerusalem colonies went up by 143% in the same time frame (OCHA, opens as PDF).

The purpose of the settlements, both those close to the Old City, as well as the ‘outer ring’ (or Jerusalem ‘envelope’) has been to make the annexation of East Jerusalem a fait accompli. As ex-deputy mayor of Jerusalem, Meron Benvenisti commented, the aim of the expropriation of land around Jerusalem just three years into the post-’67 occupation was “to encircle the city with huge dormitory suburbs ‘that would obviate any possibility of the redivision of Jerusalem’”.

Israel’s annexation of land around Jerusalem almost tripled (PDF) the land under the city’s municipal authority. A third of the annexed land was expropriated for settlements, and over forty years, more than 50,000 housing units were built for the Jewish population on this land; none, of course, for Palestinians.

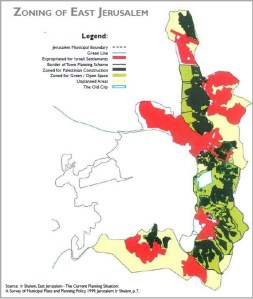

From 2000 to 2009, Israel confiscated PDF) over 40,000 dunams in Jerusalem; just under two-thirds of that total was taken in the last five years (’05-’09). In April last year, the UN OCHA reported (PDF) that only 13% of the Israeli-annexed area of East Jerusalem is ‘zoned’ for Palestinian construction (if permission is obtained).

‘Zoning’ land in East Jerusalem for particular purposes is an important way that Israel limits the natural growth of the Palestinian population. Some areas are declared ‘Green’, meaning no building is permitted there. In Jabal Mukaber, for example, 15,000 Palestinian residents are kept to 20% of the neighbourhood’s land, with the rest marked ‘Green’. However, there are a number of settlements that were built on land previously zoned as ‘Green’.

Targeting Palestinian neighbourhoods

Another strategy that has recently come under the spotlight is the targeting of Palestinian communities in East Jerusalem by extremist religious settler movements. In Sheikh Jarrah, Palestinians are being evicted from their homes in order for religious Jews to move in, a phenomenon described by ex-Tourism Minister – and supporter of the settlers – Benny Elon as “a microcosm of the entire story of Jerusalem”.

(Elon has highlighted Jewish settlement in Sheikh Jarrah as part of a plan “to create a Jewish continuum surrounding the Old City”, with other methods including “declaring open areas to be national parks and placing state property back-to-back with lands under Jewish ownership”.)

The irony about the Sheikh Jarrah evictions is that the settlers are making their case in the courts based on a claim of pre-1948 ownership. Palestinians dispossessed in the Nakba would not be hopeful of regaining their property on the same basis – whether in West Jerusalem or elsewhere.

Is not it absurd that the very same Palestinian whose property was confiscated in 1948 finds that his new home is confiscated on the grounds that it was owned previously to 1948 by Jews? What is it precisely that distinguishes the claim of the Jew from that of the Palestinian?

Uri Bank, a political activist for the extreme-right Moledet party, described the process and objective in comments made in 2003: “We break up Arab continuity and their claim to East Jerusalem by putting in isolated islands of Jewish presence in areas of Arab population…Our eventual goal is Jewish continuity in all of Jerusalem.” Ariel Sharon once boasted that the “goal” was “not leaving one neighbourhood in East Jerusalem without Jews”.

Meanwhile, archaeological excavations are delegated by Israeli authorities to ideologically-driven right-wing Jewish groups. Silwan is home to the ‘City of David’ project, a tourism-oriented initiative of the settler group Elad. Dozens of Palestinian homes in Silwan are threatened with demolition, while Jerusalem mayor Nir Barkat hopes to develop the area “in terms of historical and religious tourism”.

In May 2009, Ha’aretz revealed that the Israeli Prime Minister’s office and Jerusalem municipality were working with settler groups to “surround the Old City of Jerusalem with nine national parks, pathways and sites”. The Jerusalem Development Authority said the aim was “to strengthen Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel”.

The Israel Lands Administration works “together with the [settlement-promoting] Ateret Cohanim association”, while the new “Samaria and Judea District Police” headquarters in the strategic E1 area received funding from both the state and right-wing Jewish groups. It is little wonder that EU consuls in East Jerusalem felt moved to accuse “the Israeli government and the Jerusalem municipality” of assisting right-wing groups in “their efforts to implement this ‘strategic vision’ [of altering the city’s demographic balance and severing East Jerusalem from the West Bank].

The road network

Planning transportation links, and particularly road networks, is a vital part of shaping the nature of how a city develops. The Jerusalem municipality understands this, and thus the roads that go through and around occupied East Jerusalem are another part of Israel’s strategy.

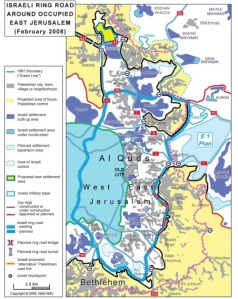

One particularly key project is the Eastern Ring Road, the idea of which is to ‘join the dots’ between Israeli colonies in East Jerusalem, and West Jerusalem. A proposed 11km section of the route goes through numerous Palestinian villages and neighbourhoods of Jerusalem, meaning the confiscation of over 1,000 dunams of land. According to a report in the Jerusalem Post in 2006, the idea of the ring road goes back some years, “and was first sketched onto maps by Ariel Sharon during his tenure as a Likud minister and planner of construction efforts designed to erase Israel’s Green Line boundary with the West Bank”.

One particularly key project is the Eastern Ring Road, the idea of which is to ‘join the dots’ between Israeli colonies in East Jerusalem, and West Jerusalem. A proposed 11km section of the route goes through numerous Palestinian villages and neighbourhoods of Jerusalem, meaning the confiscation of over 1,000 dunams of land. According to a report in the Jerusalem Post in 2006, the idea of the ring road goes back some years, “and was first sketched onto maps by Ariel Sharon during his tenure as a Likud minister and planner of construction efforts designed to erase Israel’s Green Line boundary with the West Bank”.

Palestinians, meanwhile, are being built ‘alternative’ roads, in order to link up different enclaves. When serving as the UN’s Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in the OPT, South African legal professor John Dugard described what he called “Israel’s broader plan to replace territorial contiguity with ‘transportational contiguity’ by artificially connecting Palestinian population centres through an elaborate network of alternate roads and tunnels and creating segregated road networks, one for Palestinians and another for Israeli settlers, in the West Bank”.

It is also important to mention the Jerusalem Light Rail, a project that has suffered setbacks on account of the international BDS movement. Once again, while the public, official purpose of the rail line is “relieving traffic congestion and renewal of the city centre”, the map of the route confirms that is another way of the Jerusalem municipality consolidating the colonisation of the eastern half of the city.

The dividing Wall

Israel’s Separation Wall cuts through occupied East Jerusalem, dividing neighbourhoods, villages, families, and streets:

The wall epitomises all the tactics of domination. It more than doubles the area of East Jerusalem, creating a clover shape to include the new settlements and their development zones: Bet Horon, Givat Zeev, Givon Hadasha and the future Nabi Samuel park; Har Gilo, Betar Ilit and the Etzion Bloc; Maale Adumim.

OCHA describes the Wall’s deliberate function of inclusion/exclusion:

The route runs deep into the West Bank to encircle the large settlements of Giv’at Zeev (pop. 11,000) and Ma’ale Adummim (pop. 28,000). These settlements currently lie outside the municipal boundary but will be physically connected to Jerusalem by the Barrier. By contrast, densely populated Palestinian areas – Shu’fat Camp, Kafr ‘Aqab, and Samiramees with a total population of over 30,000 – which are currently inside the municipal boundary, are separated from East Jerusalem by the Barrier.

The Wall has created an enclave in Bir Nabala, where 15,000 Palestinians are surrounded. There are now some 50,000 Palestinians with Jerusalem residency who find themselves on the wrong side of the Wall.

Palestinians: immigrants in their own city

The Palestinians of East Jerusalem have ‘permanent residency’ status from the Israeli authorities. They are not citizens. In fact, as Attorney Yotam Ben-Hillel put it, Palestinians of East Jerusalem “are treated as if they were immigrants to Israel, despite the fact that it is Israel that came to them in 1967”.

The next time someone tells you that Israel is the ‘only democracy in the Middle East’, ask them why there are over 100,000 children in Jerusalem who were born without citizenship.

A Palestinian ‘resident’ does not need a permit to live and work in Israel, and is also entitled to health insurance and other social rights. However, ‘residents’ do not have the right to vote in national elections, can not automatically pass this status on to their children, and, are liable to having their ‘permanent residency’ revoked – which can happen without appeal or even notification.

In 2008, Israel stripped over 4,500 Palestinians in East Jerusalem of their residency status, which is a third of the total revocations since 1967. A leaked EU Heads of Mission report in 2005 observed that when it comes to the residency status policy, “Israel’s main motivation is almost certainly demographic”.

Restricting home construction

A fundamental part of Israel’s strategy in East Jerusalem is to restrict the ability for Palestinians to build or expand their houses, which restricts the growth of the community and also makes for conditions in which normal life becomes increasingly untenable.

The Jerusalem municipality’s discriminatory approach to housing means that as many as 40% of houses in East Jerusalem are ‘illegal’, because they were built without having received the proper building permit. Permits, like in ‘Area C’ of the West Bank, are routinely denied – an EU report last year noted that Silwan had received only 20 building permits since 1967. The process of applying is also highly – often prohibitively – costly: over $25,000 for a 200 sq metre building. In 2009, over 900 demolition orders for Palestinian houses were issued by the Jerusalem municipality, with dozens carried out.

The Israeli newspaper Yediot Yerushaliyim reported in April of last year that the Jerusalem municipality “intends to spend 1.2 million shekels on aerial photographing to track building offenders, in the eastern part of the city in particular”. Earlier this month, Ha’aretz referred to the existence of a NIS 2 million budget “for demolishing and sealing off illegal structures”.

While encouraging and facilitating intensified colonisation of East Jerusalem, Mayor Nir Barkat sometimes feels compelled to make positive noises about providing solutions to the ‘Arab housing shortage’. Yet even when Barkat announced plans for new houses, over two-thirds of the units will take 20 years to complete – by which time, there will be a 74% shortfall in Palestinian housing needs.

The death of Palestinian East Jerusalem and Israeli ‘democracy’

It is not difficult to understand the rationale behind the outworking of the permit system and the demolitions, or to see the vision at work behind all the various policies covered briefly here. Teddy Kollek, mayor of Jerusalem from 1965 to 1993, quotes government officials in his 1994 book as saying that, “[It is necessary] to make life difficult for the Arabs, not to allow them to build…” An engineer and chief planner for the municipality once confirmed that the “only way to manage” the ratio between the Palestinian and Jewish population is “[through manipulation] of housing potential]”.

Amir Cheshin served as senior advisor on ‘Arab Affairs’ for ten years under Kollek and then Ehud Olmert. The book he went on to co-author does not shy away from the reality of Israel’s policies in East Jerusalem:

Kollek spearheaded the effort by Israel to settle east Jerusalem with Jewish families. In 1970 Kollek coauthored the proposal for development in east Jerusalem that became the basis for Israeli policy for the next decade. Indeed, the 1970 Kollek plan contains the principles upon which Israeli housing policy in east Jerusalem is based to this day – expropriation of Arab-owned land, development of large Jewish neighbourhoods in east Jerusalem, and limitations on development in Arab neighbourhoods.

This month, Jerusalem mayor Nir Barkat described the Palestinians in East Jerusalem as a “strategic threat”, at a meeting of a Knesset lobby group. Barkat worried about the percentages, and the difficulty of keeping the Palestinians at 30% of Jerusalem’s population, the apparent goal. As ex-deputy mayor Benvenisti says, “It’s pure racism. We live in the only city in the world where an ethnic population ratio serves as a philosophy”.

In the words of the director of Israel’s Macro Centre for Political Economics, in order “to try to guarantee a Jewish majority and generate Jewish hegemony in Jerusalem”, Israel “has annexed huge parts of Jerusalem, enlarged the boundaries of the municipality, taken lots of land in the eastern part of the city and built more than 50,000 housing units on this land exclusively for Jews”.

This overview of Israel’s deliberate colonisation of East Jerusalem in defiance of international law only begins to scratch the surface. In the international ‘peace process’ and associated media reports, Jerusalem is typically presented as a ‘final status’ issue in the negotiations to establish a Palestinian state. Through policies going back 40 years, Israel’s leaders from across the political spectrum have made it clear that as far as they are concerned, Jerusalem’s ‘status’ is already final.

APJP | Comments Off |

APJP | Comments Off |