Israel unveils Herod's archaeological treasures

Wednesday, February 13, 2013 at 11:25PM

Wednesday, February 13, 2013 at 11:25PM http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/feb/12/israel-archaeological-exhibition-herod-the-great

Herod's mausoleum headlines Israel's most ambitious archaeological show but Palestinians say treasures should stay where they were found

Harriet Sherwood in Jerusalem 12 February 2013

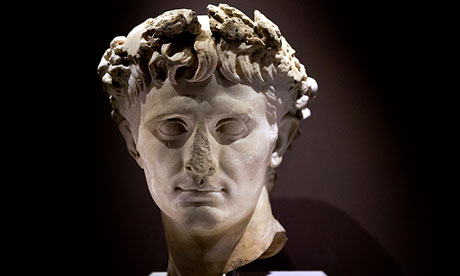

A magnificent mausoleum in which King Herod the Great, the biblical-era ruler of Jerusalem and the Holy Land, was laid to rest at the end of his 37-year reign of terror is the centrepiece of the most ambitious archeological exhibition ever mounted in Israel.

Herod's burial chamber, discovered less than six years ago after a 40-year search, has been reconstructed within the Israel Museum in Jerusalem for the first ever exhibition to focus on the murderous king. Thirty tonnes of artefacts were excavated from the site of the tomb, the desert palace of Herodium, situated near the West Bank city of Bethlehem, for the eight-month show, Herod the Great: The King's Final Journey.

During his bloodthirsty tyranny, he executed at least one of his wives and three of his sons as well as countless rabbis, opponents and people who simply got in his way. According to Matthew's gospel, he ordered the killing of all newborn babies following the birth of Jesus, although some scholars say his son, also called Herod, was responsible for the butchery (and others dispute it happened at all).

An ornate red flower-carved sarcophagus, believed to be Herod's, which was discovered smashed into rubble, has been painstakingly pieced together for the exhibition. In total, around 250 archaeological finds are on display, alongside models and graphic displays of his palaces.

Herod's death at the age of 70 followed an excruciating illness. According to Simon Sebag Montefiore, "Herod collapsed, suffering an agonising and gruesome putrefaction: it started as an itching all over with a glowing sensation within his intestines, then developed into a swelling of his feet and belly, complicated by an ulceration of the colon.

"His body started to ooze clear fluid, he could scarcely breathe, a vile stench emanated from him, and his genitals swelled grotesquely until his penis and scrotum burst out in suppurating gangrene that then gave birth to a seething mass of worms."

His body was taken from Jericho to Herodium to be entombed on his man-made mountain. The mausoleum was discovered in May 2007 by Ehud Netzer, an Israeli archaeologist who had devoted his career to searching for it.

Three years later, during the first visit to the site by the Israel Museum's curators and restorers, Netzer fell to his death after leaning on a barrier. The exhibition is dedicated to his memory.

The show has met with opposition from the Palestinian Authority (PA), which says Israel is in breach of international law by exhibiting artefacts excavated and removed from the West Bank.

Hamdan Taha, a PA official responsible for antiquities, said the Israel Museum had not consulted it on the excavation and exhibition. Herodium is located in Area C of the West Bank, which is under full Israeli control, and the site is administered by the Israeli Parks Authority.

The exhibition was an attempt to use "archaeology to justify Israel's political claims on the land", Taha said. The site, along with Jericho, was "an integral part of Palestinian cultural heritage", he added.

The Israel Museum said that Israel was given temporary control over archaeological sites in the West Bank under the 1993 Oslo accords, and that the museum had co-ordinated with the Israeli Civil Administration, which governs Area C.

"We have this material on loan, and it will be returned to the site after the exhibition," said James Snyder, director of the Israel Museum. "Everything is here on an authorised basis. If we had left [the artefacts] as they were, there was no way of understanding or interpreting them. We are not about politics or geopolitics; we are trying to do the best and the right thing for the long-term preservation of material cultural heritage."

Yonathan Mizrachi, of Emek Shaveh, an Israeli organisation that focuses on the role of archaeology in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, said international law did not permit the removal of artefacts from occupied territory. Excavated material "should be kept in the West Bank and [Palestinian] residents must have access".

The exhibition, he added, would have "a major political effect on Israeli public opinion about Jewish heritage and will strengthen claims to the land".

-

More on this story

-

World's first King Herod exhibition opens in Jerusalem - video

Jerusalem's Israel Museum launches the world's first exhibition on the life and legacy of the ancient Roman King Herod the Great on Tuesda

APJP | Comments Off |

APJP | Comments Off |