We can’t lose a democracy we never had

Monday, August 12, 2013 at 03:48PM

Monday, August 12, 2013 at 03:48PM http://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-1.539584

The illusion of democracy in Israel is just one of the many illusions that we Israelis have been educated to believe.

By Tsafi Saar 4 Augist 2013 Haaretz

Many dirges have been heard lately lamenting the death of democracy on account of the governability law that passed its first reading in the Knesset this past week. There is reason to lament; it is indeed a bad and dangerous piece of legislation. But for something to die, it must have once lived. Has there been democracy in Israel before the governability was passed? The answer is no. For Israel's entire 65-year existence it has not been a democratic state. From its founding until 1966 Israel imposed martial law on the Arab communities in its territory. Since the occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967 until today, Israel has ruled over millions of Palestinian inhabitants in these territories – an occupied population with its basic freedoms and rights abrogated.

There has been an illusion of democracy here, or alternatively, a democracy for Jews only. This of course is a contradiction in terms. This is just one of the many illusions, which we Israelis have been educated to believe. It isn't easy to discover how much of life and education here are full of indoctrination, because lightly scratching the surface reveals what is just a cover for an entirely different reality. Some of us discover this at an early age, others later. There are also those who will never discover this, perhaps they would even prefer not to see it.

Among the prominent examples are myths like "making the desert bloom," or the statement, "A land without a people for a people without a land" - basic concepts in Zionism that express a worldview that ignored the land's inhabitants. There is "Hebrew labor," the aspiration that Jews who settled the land would work with their own hands instead of managing others, which is perceived to be something positive until we understand that it means excluding native Arabs from work. Another phenomenon placed on a pedestal is the revival of the Hebrew language. While it was a blessed miracle, it also was enabled by the pushing aside of many other languages as well as other cultures, not infrequently with violence – and this already sounds less heartwarming.

There are also clichés like "our hand is outstretched in peace," as our politicians are wont to say while they are still polishing up ruins. In other versions, still in use today, there are mantras like "no partner for peace." And who can forget "the world's most moral army"? The same army that just recently detained a 5-year-old Palestinian child for investigation, and the state that plans to evict 1,300 Palestinians from their homes in the south Hebron hills to save time and resources, just to mention two examples among countless others.

These are bothersome thoughts. Is it possible that everything we were raised on, or at least most of it, is mistaken? What is the significance of this? And does asking these questions undermine the fact of our existence of here? If our existence here must be based on a strong fist, on pushing out others, on nationalism, chauvinism and militarism, then the answer is yes. But is this really the case?

In the history of Zionism there were other options besides that of Ben-Gurion-style force. For example, the path shown by professors Zvi Ben-Dor Benite and Moshe Behar in their recently published book "Modern Middle Eastern Jewish Thought: Writings on Identity, Politics, and Culture." Jewish intellectuals of Middle Eastern origin at the beginning of the 20th century warned against adopting a European arrogance to the land's inhabitants and called for respectful dialogue with them. But their words fell on deaf ears. The Brit Shalom faction of Hugo Bergmann and Gershom Scholem also proposed another way in the 1930s that was not accepted.

The state established here was not, despite its pretensions, "the sole democracy in the Middle East." It appears that the first condition for really fixing this situation, if that is still possible, is the recognition that we did not lose democracy now. It never resided here.

*******************************************************************************

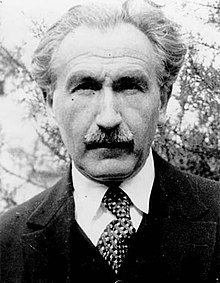

The path not taken; Left, Hugo Bergmann co-founder of Brit Shalom, 1925-48, which advocated “dual-national” areas where Jews and Arabs could live under equal conditions. Right, Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, co-author of a book on modern middle-eastern Jewish thinkers who warned against Jews adopting “a European arrogance to the land’s inhabitants”.

Notes and links

Brit Shalom (Covenant of Peace)

Founded in Palestine in 1925 as a pressure group for peaceful coexistence between Arabs and Jews to be achieved by renunciation of the Zionist aim of creating a Jewish state. It advocated a bi-national state. Henrietta Szold , Arthur Ruppin, Martin Buber, Hugo Bergmann, Gershom Scholem, Albert Einstein and Judah Magnes were among their members or supporters.

From The History of the original Brit Shalom, founded 1925

“If we do not give every member of the public the opportunity of considering the Jewish-Arab question, we will be committing, I think, an unpardonable sin. Why do I think so? For two reasons. First: it was Judaism, which brought me to Zionism and I cannot but believe that Judaism, Religion as I understand it, is our moral code; and Judaism bids us to find a way in common with the Arabs living in this country. Secondly: I am almost certain that at the end of the war it will not be easier that it is now to shape the development of our life in the way we desire by bearing our influence on those who determine the course of affairs. The more I return to this matter, the more do I become convinced that politically as well as morally, the Jewish-Arab question is the decisive question. I insist that we must reach an understanding of this question, and we can succeed in this only if we are offered opportunities of meeting and discussing the matter. I think that even at this late hour we must endeavour, through IHUD, to find ways of speaking and conferring about this question with clear insight and full knowledge of its importance. And that paragraph of national discipline printed on the Shekel cannot deprive us of the right to speak and understand.”

Henrietta Szold (1942)

Modern Middle Eastern Thought: Writings on Identity, Politics, and Culture, 1893–1958, Edited by Moshe Behar and Zvi Ben-Dor Benite

Published by Brandeis University Press and University Press of New England, 2013

Blurb from The Tauber Institute, Brandeis university

Moshe Behar and Zvi Ben-Dor Benite present Jewish culture and politics situated within overlapping Arabic, Islamic, and colonial contexts. The authors invite the reader to reconsider contemporary evocations of Levantine, Mizrahi, and Arab Jewish identities against the backdrop of writings by earlier Middle Eastern Jewish intellectuals who critically assessed or contested the implications of Western presence and Western Jewish presence in the Middle East; religion and secularization; and the rise of nationalism, communism, and Zionism, as well as the State of Israel.

Moshe Behar and Zvi Ben-Dor Benite present Jewish culture and politics situated within overlapping Arabic, Islamic, and colonial contexts. The authors invite the reader to reconsider contemporary evocations of Levantine, Mizrahi, and Arab Jewish identities against the backdrop of writings by earlier Middle Eastern Jewish intellectuals who critically assessed or contested the implications of Western presence and Western Jewish presence in the Middle East; religion and secularization; and the rise of nationalism, communism, and Zionism, as well as the State of Israel.

APJP | Comments Off |

APJP | Comments Off |