Losing battle with IDF, Palestinians in firing zone face largest expulsion since ’67

Friday, August 12, 2022 at 04:58PM

Friday, August 12, 2022 at 04:58PM Masafer Yatta’s eight villages set to be cleared out after a 20-year court fight, despite evidence showing homes predating training area and questions over army’s motivations

by Aaron Boxerman 12 August 2022 Times of Israel

FAKHIT, West Bank – In a cluster of dusty hamlets south of Hebron, a decades-long contest of wills between Palestinians and the Israeli government may be coming to an end.

After a legal battle lasting over 20 years, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled in early May that the army could evict over 1,300 Palestinians living inside a military training zone that covers miles of rolling hilltops.

“They’re trying to remove us from here, once and for all,” said school principal Haytham Abu Sabha, who says he has lived in this village his entire life.

If carried out, it would be the largest single eviction in the West Bank since Israel captured the territory in the 1967 Six Day War, according to the Association for Civil Rights in Israel.

Fakhit is just one of nearly two dozen Palestinian hamlets that dot Masafer Yatta, the Arabic name for the sprawling hills south of Hebron. About eight would be cleared under the ruling. Local Palestinians work as herders and farmers, raising goats and sheep, who graze on the scrubby hillsides.

In 1979, the army expropriated some 30 square kilometers (11.5 square miles) of land and declared it Firing Zone 918. Since then, the Israeli military has sought to evict Palestinians living in eight villages that lie inside the firing zone, most of them collections of low-slung homes with makeshift roofs.

Local Palestinians argued that their presence predates the firing zone, meaning that they cannot be expelled under Israeli law.

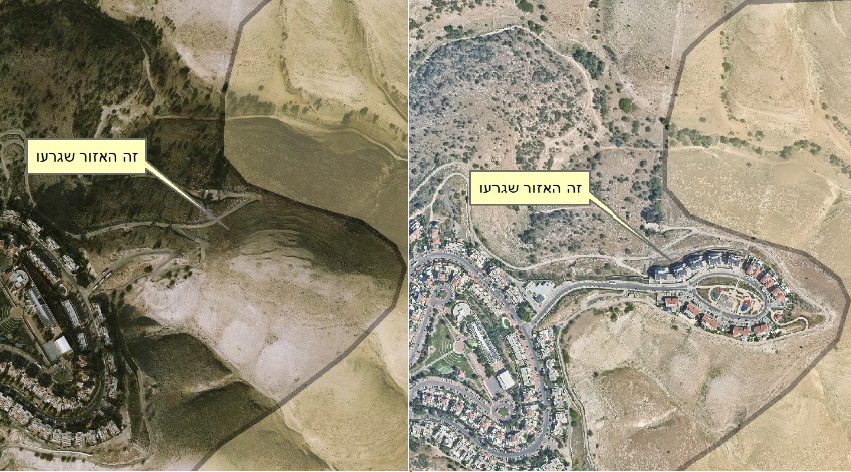

Israeli authorities contest the Palestinians’ argument and government attorneys have presented satellite photos they claim show no residential structures on the hilltops before the 1990s.

“They never lived there. You don’t see, for example, consistent agricultural cultivation or orchards [in satellite photos]…There are no permanent houses that are clear and visible to the eye,” said Kobi Eliraz, a former senior Defense Ministry adviser on settlement affairs.

“Palestinians know that they can steal land from Jews, so they go ahead and do so,” Eliraz alleged.

But Palestinians say the homes were not visible because of their unique way of life: using roomy caves as homes and cultivating flocks on the hillsides. An anthropologist, Yaakov Habakuk, chronicled the unusual homes in a contemporaneous account.

“I myself grew up in a cave. Some of the happiest days of my childhood were spent there,” attested a resident of the nearby village of Tuba who preferred not to be publicly identified.

Left-wing rights groups have backed the Palestinian residents. According to Alon Cohen-Lifshitz, an urban planner at the Bimkom nonprofit, a closer examination of the images shows the cave homes and other structures clearly.

Since the firing zone was declared in the early 1980s, Israeli authorities had demolished illegally built structures in the area. But in 1999, the Israeli army decided to evict the Palestinians living in the area once and for all.

Around 700 Palestinians were moved to areas at the edge of the firing zone. Many of the villages’ structures were demolished and some of the caves were filled in with concrete, said Abu Sabha, the school principal. The Palestinians, backed by the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, appealed to the High Court.

For over two decades, both sides fought it out before the justices’ bench. In the meantime, Palestinians living in Masafer Yatta were forced to live in a state of limbo.

All new construction was illegal, but Palestinians continued to build new homes and agricultural structures to support their burgeoning population. Israeli bulldozers razing houses became a regular sight.

“One cannot receive permits in a firing zone. The [Palestinian] petitioners have been caught in a trap for 22 years,” said Dan Yakir, an attorney at the Association for Civil Rights in Israel.

As they were built in a firing zone, village homes could not be legally hooked up to electricity or water. Palestinians made do by affixing solar panels or using generators, which were occasionally confiscated by the army as well.

Just outside the firing zone, Israeli outposts – also built illegally under Israeli law – sprouted up on the nearby hilltops. The settlers, unlike the Palestinians, enjoy access to running water and electricity in their homes.

According to Cohen-Lifshitz, settlers have quietly expanded into the edges of the firing zone as well, including small agricultural buildings and roads leading to three local outposts – Havat Maon, Avigayil and Mitzpe Yair.

“There’s a widespread trend of settlements next to the firing zone spreading into the zone itself, in total contravention of the restrictions imposed by firing zones,” wrote Cohen-Lifshitz of the three outposts.

Palestinians say the settlers who populate the outposts harass them on a regular basis. Some of the most brazen Jewish extremist violence in recent years – including a crowd that hurled stones at cars and homes last September, wounding a three-year-old Palestinian boy – has taken place in the area.

“The Israeli authorities are working to make our lives here unbearable. It would be too embarrassing [to expel us], so they deprived us of basic rights in the hopes we would pick up and leave,” said Abu Sabha.

“But now they’ve realized that it won’t work. We imposed our own facts on the ground during the last 20 years,” he added.

Finally, at midnight on May 3 – Israel’s Independence Day – the court quietly coughed up the ruling. The justices decided that the army could expel the Palestinians, wrote Judge David Mintz for the majority.

Mintz upheld the army’s determination: the Palestinians had not been permanent residents, but rather seasonal herders who flitted in and out of the hilltops with their flocks.

“No signs of habitation can be observed in the area prior to 1980, certainly not permanent habitation in the entire area,” wrote Mintz, saying the army had provided “a clear evidentiary picture.”

Mintz criticized the Palestinians for continuing to build structures in their villages in the meantime, saying they had abused the legal process to build.

“Taking the law into one’s own hands and seeking equitable relief are incompatible,” Mintz said.

Local settler leader Yochai Damari, who chairs the Hebron Hills regional council, hailed the decision. He slammed the Palestinians for residing in lands expropriated by the army.

“They’re not meant to be on state land. They’re squatters, and this is why the High Court ordered them to evacuate [the area]. I salute this, as we are fighting for the territory of our country,” Damari said in a video message posted to his Facebook page.

Zoned out

In the courtroom, both the army’s attorneys and Palestinian advocates framed their arguments within a host of technical considerations prescribed by law. They argued over everything from when the Palestinians arrived in the area to how often the army used the terrain.

Outside the hallowed High Court walls, however, both Israeli settlers and Palestinians view the struggle over the rolling hillsides as part of the national tug-of-war over the future of the West Bank.

Palestinians and left-wing Israelis hope to see the region become part of a Palestinian state, an idea opposed by the Israeli right. Both sides see the mostly empty Area C – where the vast majority of Israeli settlements are also located – as a critical battleground. Both sides accuse the other of seeking to create facts on the ground.

Damari, the settler council head, called the decision “good for the settlement enterprise, good for state land, good as regards the battle for Area C that we are so heavily involved in.”

About 18 percent of the West Bank is taken up by military training zones, according to the left-wing Kerem Navot nonprofit. The Israeli army says it uses the zones to conduct essential training operations.

“The vital importance of this firing zone to the Israel Defense Forces stems from the unique topographical character of the area, which allows for training methods specific to both small and large frameworks, from a squad to a battalion,” attorneys for the Israeli military told the High Court during one of the endless rounds of hearings on Masafer Yatta.

But archival documents from the early years of Israeli rule in the West Bank suggest another motivation for declaring the local firing zones may have been to ensure full Israeli control of the area.

In a 1981 meeting of the government’s Settlement Committee, future prime minister Ariel Sharon said firing zones in the South Hebron Hills were necessary to ensure the area remained in Israeli hands.

“We have the idea that we must close off more training zones on the border, at the Hebron foothills towards the Judean desert. [This is] in light of the phenomenon I discussed earlier — that of rural hill Arabs spreading out on the hill towards the desert,” said Sharon, a longtime advocate of Israeli settlement.

Sharon’s committee sent a formal recommendation to the Israeli military that a firing zone be declared in the south Hebron hills. Firing Zone 918 was conceived soon afterwards.

The Palestinians’ lawyers submitted the meeting minutes as evidence during the High Court hearings. The justices, unswayed, dismissed the remarks in their ruling as too general to be used.

In at least two cases, Israeli officials have amended or proposed moving the boundaries of firing zones to adjust for Israeli settlement construction.

In 2015, then-Israeli West Bank commander Nitzan Alon signed an order removing around 200 dunams from Firing Zone 912, which lay adjacent to the settlement of Ma’aleh Adumim, according to documents seen by The Times of Israel. The area is now built up with houses clearly visible in satellite imagery.

In the northern West Bank, the Israeli government said in court filings that it is considering moving the boundaries of Firing Zone 904a to accommodate two illegal Israeli outposts built in the area, Itamar’s Farm and Givat Arnon.

The filing came after Palestinians from nearby Khirbet Tana petitioned Israel’s High Court, asking why their homes were set for imminent demolition, while the illegal Israeli outposts, within the same firing zone, were not.

“The political echelon asked the relevant army officials to remove the land on which the two outposts are located from the firing zone,” the army responded, telling the court that it was still looking into the matter.

‘Red lines’

The May court ruling gave the military the green light to evict the Palestinians. But that does not mean that Israeli authorities necessarily will do so.

The transitional Israeli caretaker government, deeply divided between right and left, may be incapable of carrying out the eviction orders.

“It would be a shame – as this is an essential, necessary, urgent step,” said Eliraz.

Left-wing Israelis also say a mass expulsion is unlikely; rights groups expect various administrative measures will slowly pressure Palestinians to leave the zone, said Shira Livne, an official at the Association for Civil Rights in Israel.

Masafer Yatta’s Palestinian residents, their arguments rejected by Israeli courts, now place their hope in a campaign of international pressure on Israel to stop the demolitions.

“We demand the international community act to end this. Since there is no justice in Israeli courts, we can go as far as the International Criminal Court,” said Younes, the local council head.

But a Western diplomat closely following the issue estimated that international pressure would have little effect on Israeli authorities should they ultimately choose to evict the Palestinians en masse.

“There are so many red lines that have been burned and nothing much happened. There will be tweets and statements. The United States will pressure from behind the scenes,” the diplomat said, speaking to The Times of Israel on condition of anonymity.

At a press conference in Washington in early June, US State Department spokesperson Ned Price reiterated American opposition to “unilateral” moves by Israelis and Palestinians, “including evictions.”

“But what can we do, honestly,” the Western diplomat said. “Nothing that can stop it.”

(There is plenty you can do! Simply apply BDS and support UN Resolutions: Ed)

______________________________________________________________________________________

Reader Comments